Born to a Protestant father and Catholic mother, Anthony "Tony" Martin was a Canadian Catholic priest who was sent to the Philippines in 1958.

Stunned by the poverty that surrounded him, he spent the last 36 years of his life trying to save the livelihood of thousands of poor Filipinos by championing the use of Credit Unions.

Credit Unions - not religion - would alleviate the suffering of the poor.

He resigned as a priest and left the Catholic Church in 1972 to spend more time recruiting Filipinos into the credit union movement.

Credit Unions, which started as a grass-roots movement in Europe in the 19th century, had been used to great effect in bringing Canadians out of poverty in Atlantic Canada. He took the lessons he learned from that area and brought it to the people of Southern Leyte.

But in doing so, Tony Martin ran into opposition from powerful political clans and money lenders who profited from the poor. "The American", as he was mistakenly called, fell into their radar and became a person they viewed with suspicion.

They considered his work of bringing social justice to the poor a threat to the current economic and political order and wanted him deported back to Canada.

In response, Tony Martin renounced his Canadian citizenship and became a Filipino citizen.

For nearly 4 decades, from the 1950s to the 1990s, Tony Martin's work in the Philippines went largely unnoticed - but it would go down as one of the most remarkable feats of any Canadian in Canadian history.

Tony Martin's leadership of the Filipinos however, would come at great personal cost. By sealing his fate with the country and its people, Tony Martin charted a course that would lead to his downfall in 1982.

Born on August 28, 1926 in Bishop's Falls, Newfoundland, Canada, Tony Martin's life was shaped by his German-Dutch Protestant father and his Irish-Catholic mother.

Not wanting to join his father in the forests of Newfoundland as a "lumberjack", he became a Catholic Priest after succumbing to his mother's domineering influence.

He found his way to Ontario and joined the "Scarboro Foreign Missions", a Canadian-based Catholic Missionary group that sent its priests to Asia, the Caribbean, Latin America, and Africa.

Joining Scarboro Missions, he later revealed, would allow him to "see the world".

After completing his theological studies at St. Augustine's Seminary in Toronto, and after a brief stint in Brooklyn, New York, Tony Martin was sent to the Philippines in 1958.

There, in the island of Leyte, he witnessed crushing poverty where farmers and their families were in continuous cycle of debt.

Malnourished children and destitute families wandering the towns begging for food destroyed Tony Martin's notion of the Philippines as a "Pearl of the Orient" island paradise.

Wanting to break this cycle and alleviate the suffering of the poor, Tony Martin mobilized the Scarboro Missions into creating 5 Credit Unions in 5 towns in Southern Leyte.

Credit Unions would help Filipinos break out of poverty by pooling their meager financial resources together and through patience, discipline, and strict fiduciary management, provide its members with low-interest loans. These loans, if handled productively, were a ticket out of poverty.

Credit Unions were also a "force multiplier". By Using the concept of "strength in numbers", the poor could save on items such as fertilizer, food, and medical insurance by buying as a group. Credit Unions greatly reduced the cost of these items and allowed the poor to have a fighting chance of improving their standard of living.

Tony Martin's message to the poor of Southern Leyte was : "The only way out of poverty, was through each other".

Starting in 1962, with the backing of Scarboro Missions, Tony Martin went about recruiting poor Filipinos and trained them to run credit unions. From the 1960s and 1970s, other credit unions would sprout up in the central region of the Philippines - mostly under the auspices of Tony Martin.

Canadians, through their donations to Scarboro Missions, helped sustain the development of these early credit unions - all of which were fragile.

Filipinos, with their delicate temperaments, fragile egos, passive-aggressive approach to dealing with conflicts, low self-esteem, a defeatest mentality, and a penchant for infighting & crab-mentality, were not an easy group to organize. But through a combination of sheer will, force of personality and the promise of financial wealth, Tony Martin kept these early credit unions from imploding.

While the success of the Canadian-led credit union movement in Southern Leyte became a powerful asset in the Philippine Catholic Church's fight against poverty, some saw it as a tool to recruit more Filipinos into the Catholic Religion. Tony Martin rejected this.

Although a Catholic priest, Tony Martin was not a zealous defender of the Catholic Faith. The memory of his Protestant father, a man he greatly respected, was still embedded in him. Tony Martin was partial to all things Catholic.

He stated in 1969, in an article in Scarboro Missions magazine, that his drive to create credit unions "was not a trick to bring people to church". This flew into the face of hardlined conservative Catholics who thought that Catholic Priests were duty-bound to recruit more Filipinos into their brand of religion.

His mantra "God does not intervene in human affairs" and "Only man can solve man's problems" drove him to promote social action over religious pageantry to fight economic inequality.

In 1972, he resigned as a Catholic Priest and left Scarboro Missions to free himself from the constraints imposed on him by his Catholic superiors - both in Canada and the Philippines - and to dedicate himself fully to establishing credit unions in the Philippines.

That same year however, the Philippines began to fall apart. Martial law was declared in 1972 after a growing communist insurgency - backed by China and the Soviet Union - disrupted the peace and order situation in the country.

Assasinations, kidnappings, and atrocities were committed on both sides of the conflict. In addition, the Philippine economy began to stagnate and crumble under the weight of a burgeoning dictatorship.

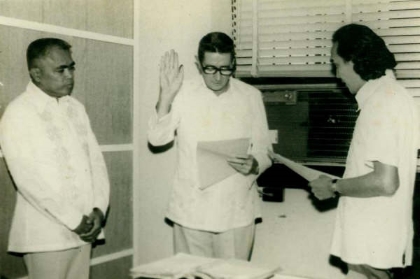

Unfazed by the chaotic environment, Tony Martin decided to share the fate of the Filipinos by becoming one of them. Tony Martin applied for a Filipino citizenship in 1976, claiming it to be essential to his work of establishing credit unions in the Philippines.

The civilian-military establishment however, had considered his work of organizing poor Filipinos into credit unions as tantamount to organizing the people along the lines of socialism and communism - two idealogical enemies of the Philippine government.

But Tony Martin argued, that credit unions were essential to rebuilding the economy. Credit Unions, like banks, were the custodians of money and he was there to steer credit unions through an economic quagmire.

Despite their suspicion of his work among the poor, the authorities admitted that they needed foreigners who had access to foreign capital and expertise; to keep the Philippines "open for business". The government thus granted Tony Martin Filipino Citizenship on April 26, 1976.

After 18 years in the Philippines, Tony Martin was no longer returning home to Canada.

What the government authorities did not realize however, was that Tony Martin had checkmated them.

By becoming a Filipino citizen, the authorities could no longer deport him back to Canada and sever him from his work of nearly 20 years in the Philippines.

Cutting off Tony Martin would mean cutting off the head of one of the most successful credit union movements to come out of the central region of the Philippines.

To strengthen and consolidate his gains and to prevent any credit unions from imploding, Tony Martin created 2 institutions - VICTO in 1970 and NATCCO in 1976.

VICTO (The Visayas Cooperative Training Organization) and NATCCO (The National Training Center for Cooperatives) were basically a "School for Credit Unions for Filipinos". VICTO and NATCCO would train the next generation of Filipinos who would run credit unions well into the next century.

VICTO would operate in the central region of the Philippines while NATCCO would oversee the entire country.

Opening a school was easy; but in a poor country, Filipinos had no money to give.

Here, Tony Martin turned to Canada for help. Scarboro Missions pitched in, as well as two other Canadian agencies - the Canadian Catholic Church's "Development & Peace" and CIDA, the Canadian International Development Agency of the Canadian Government.

When additional funds were needed, Tony Martin turned to Germany for help. The Germans were already in the Philippines doing social work and had crossed paths with the Canadians in certain regions of the country.

Two German donors - MISEREOR ("Mercy") and F.E.S. (Friedrich Ebert Stiftung Fund) stepped in to help prop up VICTO & NATCCO.

For over 10 years, Tony Martin would funnel thousands of dollars of German and Canadian foreign aid money into VICTO and NATCCO.

Over the next 30 years, thousands of Filipinos would go through VICTO and NATCCO and learned all the basic skills of running credit unions. VICTO and NATCCO became two of the most successful grass-roots based non-government organizations to come out of the 1970s.

In 1982 however, the Filipino culture reared its ugly head after the financial successes of these institutions changed the nature of the relationship Tony Martin had with the Filipinos. Tony Martin was struck down from his post as leader of VICTO and NATCCO after charges of accounting irregularities were thrown against him.

Betrayed by a handful of his Filipino colleagues who had taken control of VICTO, and stunned by the speed of which he was removed, Tony Martin tried as best he could to fight back against the accusations of mismanagement. He realized, much to his horror, that the Filipinos who had taken control of VICTO had effectively barred him from defending his case to the Board of Directors and Shareholders.

After working in the country for 24 years, Tony Martin finally became a victim of the "Crab Mentality" - a toxic Filipino trait that hovers below the warm & friendly facade that Filipinos exhibit to foreigners.

Motivated by envy & hate for any Filipino more successful than they are, the "Crab- Mentality" permeates through any familial, social or professional relationship that Filipinos have with one another - tearing apart the fabric that holds Filipino societies together.

This destructive cultural trait was one of the main problems Tony Martin faced when organizing those early credit unions in Leyte in the 1960s - and it had the power to destroy anything he built.

Now, he was at the receiving end of it. It effectively destroyed his career with the credit union movement in the Philippines.

The bitter irony of this episode of Tony Martin's life, was that in the end, he found himself an outcast from a movement that he started.

Adding to the pain of his defeat, and one that eventually crushed his spirit, was the consequence of severing ties with Canada.

No longer a priest with the Scarboro Missions, or under the protection of the Canadian government, Tony Martin realized that he was alone and powerless to do anything. He found no Canadian allies who would back him up in this fight.

After realizing that the Filipinos who had taken over VICTO had gained the upper hand through cunning legal means, Tony Martin gave up the fight and withdrew from the credit union movement. He spent the last 14 years of his life barely scraping by in the Philippines.

His struggles during this period is covered in great detail in his upcoming biography.

Despite a stellar and exemplary contribution to the country, Tony Martin's final years in the Philippines were crowned with this defeat. He died on October 21, 1994 and was buried in Cebu City, the Philippines.